It is easy to give an excess of salt and water but very difficult to remove them. Serum sodium may fall due to excess water load. Inadequate filling may lead to poor organ perfusion.

In sick patients with leaky capillaries, fluid retention contributes to complications such as ileus, peripheral oedema, pressure sores, poor mobility, pulmonary oedema, poor wound healing and anastomotic breakdown.

Urine output naturally decreases during illness or after trauma such as surgery due to increased sodium retention by the kidney. Intravenous (IV) fluid makes this worse. Cellular dysfunction and potassium loss result. Excess chloride leads to renal vasoconstriction and increased sodium and water retention. Urine output is a poor guide to fluid requirements in sick patients and oliguria does not always require fluid therapy (full assessment is required).

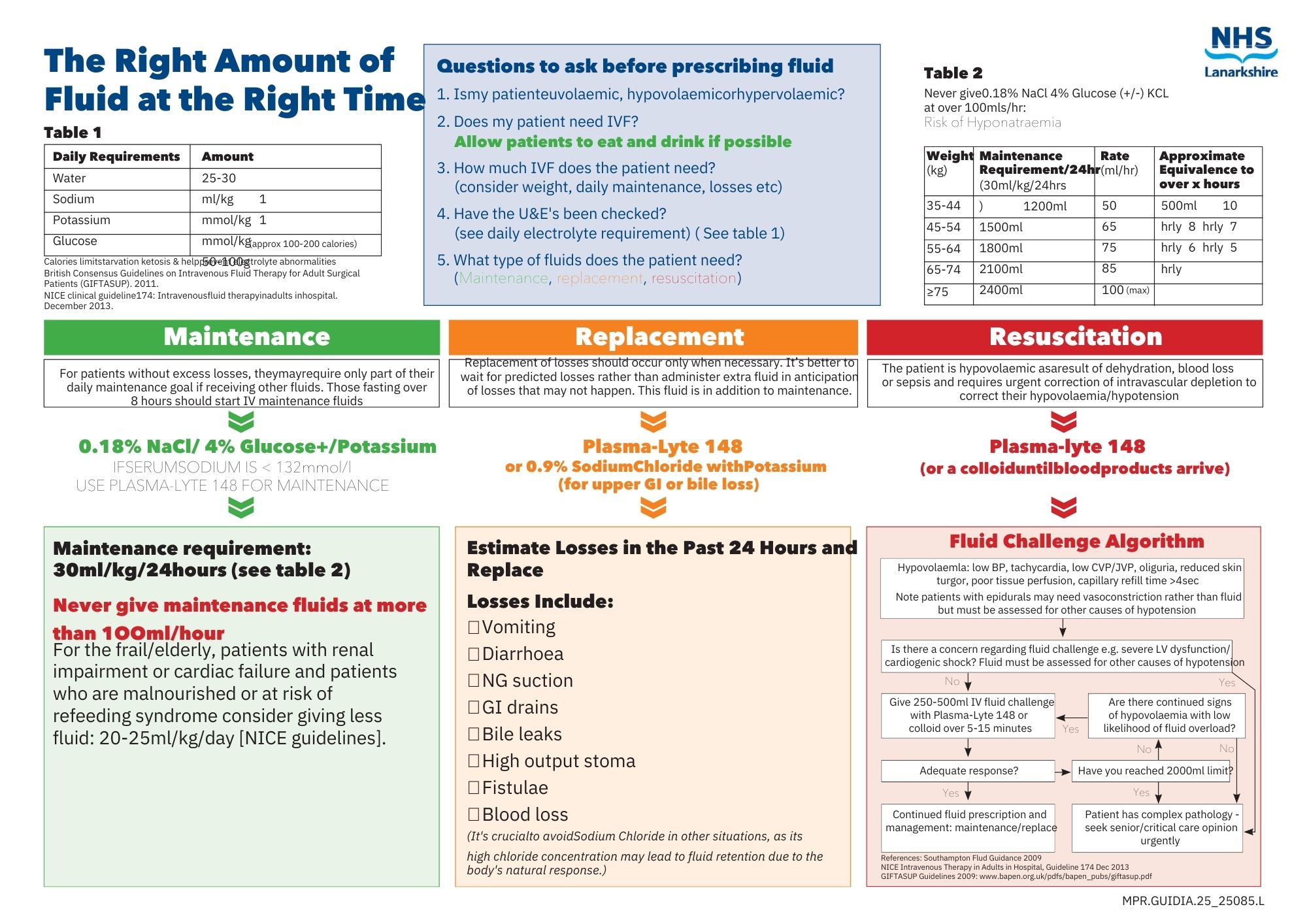

Maintenance requirement: 30ml/kg/24hours of ‘water’

It is vital that sick patients receive

THE RIGHT AMOUNT OF THE RIGHT FLUID AT THE RIGHT TIME.

Questions to ask before prescribing fluid:

1. Is my patient euvolaemic, hypovolaemic or hypervolaemic?

2. Does my patient need IV fluid? Why?

3. How much?

4. What type(s) of fluid does my patient need?

1. Assess the patient

Euvolaemic: veins are well filled, extremities are warm, blood pressure and heart rate are normal.

Hypovolaemic: Patient may have cool peripheries, respiratory rate>20, systolic BP<100mmHg NEWS>/=5, HR>90bpm, postural hypotension, oliguria and confusion. History of fluid loss or low intake. May respond to 45˚ passive leg raise. Consider urinary catheter in sick patients. However, signs of hypovolaemia may be unreliable in elderly patients.

Hypervolaemic: Patient is oedematous, may have inspiratory crackles, high JVP and history/charts showing fluid overload.

2. Does my patient need IV fluid?

NO: They may be drinking adequately, may be receiving adequate fluid via NG feed or TPN, or may be receiving large volumes with drugs or drug infusions or a combination.

Hypervolaemic: may need fluid restriction or gentle diuresis.

YES: not drinking, has lost, or is losing fluid.

ALLOW PATIENTS TO EAT AND DRINK IF POSSIBLE

So WHY does the patient need IV fluid?

Maintenance fluid only – patient does not have excess losses above insensible loss/urine. If no other intake he needs approximately 30ml/kg/24hrs. May only need part of this if receiving other fluid. Patients having to fast for over 8 hours should be started on IV maintenance fluid.

Replacement of losses, either previous or current. If losses are predicted it is best to replace these later rather than give extra fluid in anticipation of losses which may not occur. This fluid is in addition to maintenance fluid. Check blood gases.

Resuscitation: The patient is hypovolaemic as a result of dehydration, blood loss or sepsis and requires urgent correction of intravascular depletion to correct the deficit.

3. How much fluid does my patient need?

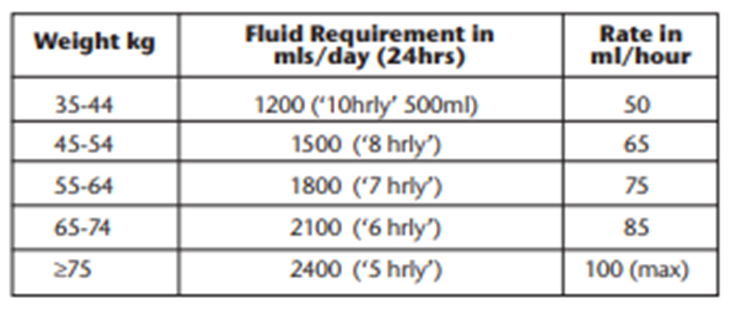

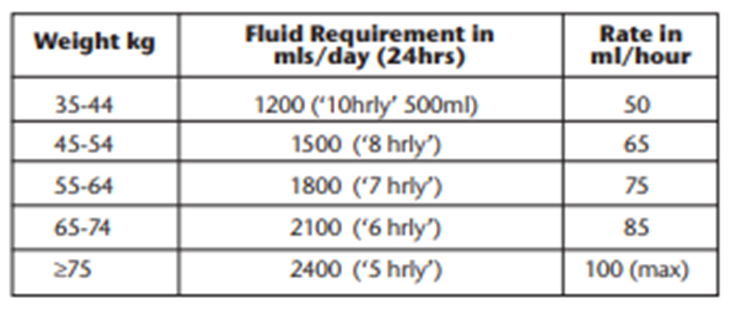

a. Obtain weight (estimate if required). Maintenance fluid requirement approximately 30ml/kg/24hours. (Table 1).

b. Review recent urea & electrolytes (U&E's), haemoglobin and other blood work.

c. Recent history – e.g. fasting, input/output, sepsis, operations, fluid overload. Check fluid balance charts. Calculate how much loss has to be replaced and work out which type of fluid has been lost: e.g. gastro-intestinal (GI) secretions, blood, inflammatory losses.

Note: urine does not need to be replaced unless excessive (diabetes insipidus, recovering renal failure).

Post-op: high urine output may be due to excess fluid; low urine output is common and may be normal due to anti-diuretic hormone release. Assess fully before giving extra fluid.

4. What type of fluid does my patient need?

MAINTENANCE FLUID

IV fluid should be given via volumetric pump if a patient is on fluids for over 6 hours or if the fluid contains potassium. Always prescribe as ml/hr not ‘x hourly’ bags.

Never give maintenance fluids at more than 100ml/hour.

Do not ‘speed up’ bags; rather give replacement for losses.

TABLE 1

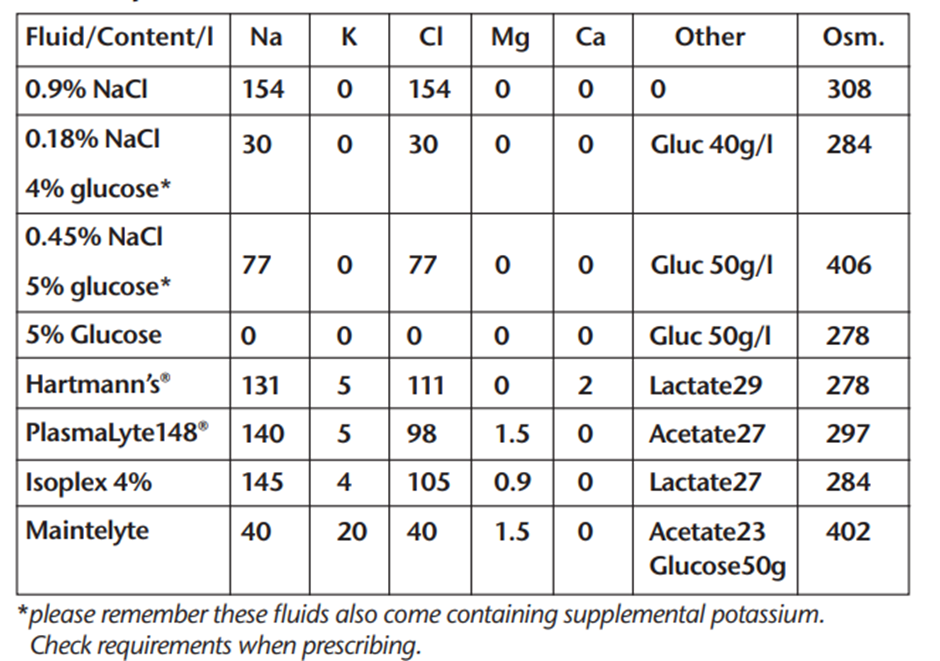

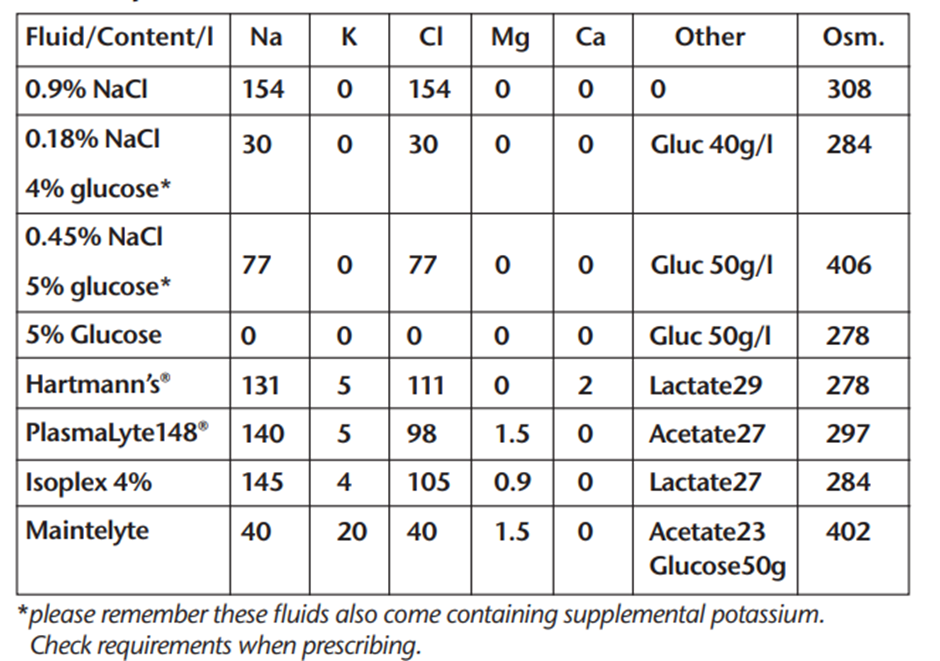

Preferred maintenance fluids: 0.18% Sodium Chloride 4% Glucose with or without added potassium 40mmol in a litre or Maintelyte. This fluid if given at the correct rate (Table 1) provides all water and Na+/K+ requirements until the patient can eat and drink or be fed. Excess volumes of this fluid (or any fluid) may cause hyponatraemia.

IF SERUM SODIM IS <132 mmol/l USE PLASMA-LYTE 148 FOR MAINTENANCE

For the frail elderly, patients with renal impairment or cardiac failure and patients who are malnourished or at risk of refeeding syndrome consider giving less fluid: 20-25 ml/kg/day (NICE guidelines).

Consult a senior doctor for fluid advice. If the serum potassium is above 5mmol/l or rising quickly, do not give extra potassium. Give Pabrinex IV if refeeding risk.

Diabetes: for those requiring variable rate intravenous insulin, give 0.45% Sodium Chloride 4% Glucose ± Potassium according to NHSL Protocol (this fluid is under review).

Electrolyte requirements

Sodium: 1 mmol/kg/24hrs

Potassium: 1 mmol/kg/24hrs

Calories: 50-100g glucose in 24 hours to prevent starvation ketosis. Consult dietician if patient is malnourished.

Magnesium, calcium and phosphate may fall in sick patients – monitor and replace as required.

REPLACEMENT FLUID

Fluid losses may be due to diarrhoea, vomiting, fistulae, drain output, bile leaks, high stoma output, ileus, blood loss, excess sweating or excess urine. Inflammatory losses (‘redistribution’) in the tissues are hard to quantify and are common in pancreatitis, sepsis, burns and abdominal emergencies. It is vital to replace high GI losses. Patients may otherwise develop severe metabolic derangement with acidosis or alkalosis and hypokalaemia. Hypochloraemia may occur with upper GI losses. Check blood gases in these patients and request chloride with U&Es.

Hyponatraemia is common: in the absence of large GI losses, causes are too much fluid, syndrope of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) or chronic diuretic use. Treatment of hyponatraemia is complex and requires senior input. A sodium of < 125mmol/l is dangerous. 0.9% Sodium Chloride or fluid restriction are first line treatments and frequent U&Es are required. See NHSL Hyponatraemia Guideline on Intranet: https://www.rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/media/1777/hyponatraemia-in-primary-care.pdf.

Potassium replacement: A normal potassium level does not mean that there is no total body potassium deficit. Give potassium in maintenance fluid. Only in critical care areas give up to 40mmol in 100ml bags via a central line at 25-50ml/hr. Ensure IV cannulae are patent and clean. Potassium containing fluids must be given via an infusion pump.

Estimate replacement fluid/electrolyte requirements by adding up all the losses over the previous 24 hours and give this volume as Plasma-Lyte 148. Use 0.9% Sodium Chloride with Potassium for upper GI or bile loss (due to high sodium and chloride contents). Otherwise avoid it as it causes fluid retention. Diarrhoea may lead to potassium loss. Normal Plasma osmolality is 285-295mosm/l.

RESUSCITATION FLUID

For severe dehydration, sepsis or haemorrhage leading to hypovolaemia and hypotension. For urgent resuscitation use Plasma-Lyte 148 or colloid (Isoplex 4%). Plasma-Lyte 148 is a balanced electrolyte solution and is better handled by the body than 0.9% Sodium Chloride.

See Fluid Challenge Algorithm Priorities: Stop the bleeding: consider surgery/endoscopy. Use Major Haemorrhage Protocol (Page 6633). Treat sepsis. CALL FOR HELP!

For severe blood loss initially use colloid or Plasma-Lyte 148 until blood/clotting factors arrive. Use O Negative blood for torrential bleeding. Severely septic patients with circulatory collapse may need inotropic support in a critical care area. Their blood pressure may not respond to large volumes of fluid; excessive volumes (many litres) may be detrimental.

IN SUMMARY: assess, why, how much, which fluid?

• Take time and consult senior if you are unsure.

• Patients on IV fluids need regular blood tests.

• Patients should be allowed food and drink ASAP