- Applies to patients aged 65 and over who present with significant injury or suspected major trauma

- Elderly patients should receive the same trauma care following admission to that given to younger patients.

- Advanced age is not an absolute predictor of poor outcomes following trauma and should not be used as the sole criterion for denying or limiting care.

- An initial aggressive approach should be pursued for management of the elderly patient unless in the judgement of an experienced consultant it seems the injury burden is severe and the patient appears moribund.

Silver trauma

Principles

Key Considerations

- Reduced physiological reserve

- Diminished physiological reserve and the presence of multiple comorbidities can mask typical signs of shock or serious injury

- A systolic BP of <110 mmHg or subtle tachycardia may be clinically significant, especially if the patient is usually hypertensive or on beta-blockers

- Multiple Comorbidities

- Conditions such as cardiovascular disease, chronic renal impairment and diabetes can complicate management

- Comprehensive medication review is crucial

- Atypical presentation

- Low-energy mechanisms (e.g. a simple fall from standing) can cause serious injuries in older adults, including intracranial bleeds, major chest injuries or spinal fractures.

- Pre-existing cognitive impairment (e.g. dementia) or delirium often obscures the clinical picture

- Anticoagulation

- Many older patients take anticoagulants or antiplatelets, increasing the risk of significant haemorrhage even with minimal trauma

- If major haemorrhage or intracranial bleeding is suspected or identified, consider reversal of anticoagulation as per local policy

- Falls

- Falls are the most common mechanism for older trauma patients. Even apparently ‘simple’ falls can result in major trauma.

- Even if initial imaging seems unremarkable, maintain a high index of suspicion. Consider advanced imaging if there is ongoing pain, abnormal exam findings or an acute change in function.

- Frailty

- Frailty scores (e.g. Clinical Frailty Score) is an independent predictor of 30-day mortality, inpatient delirium and increased care level at discharge in older people experiencing trauma. The CFS should be used to proactively identify those at risk of poor outcomes who are likely to benefit from comprehensive geriatric assessment.

- Frailty should guide early MOE input, hospital admission planning and rehabilitation strategies

- Multidisciplinary care

- Liaising with frailty/MOE clinicians, therapists, social workers and specialist nurses is crucial to ensure holistic assessment (medical, functional and psychosocial)

- Early and repeated discussions about goals of care, advanced directives, treatment escalation plans (including DNACPR) and patient (or family) preferences are essential.

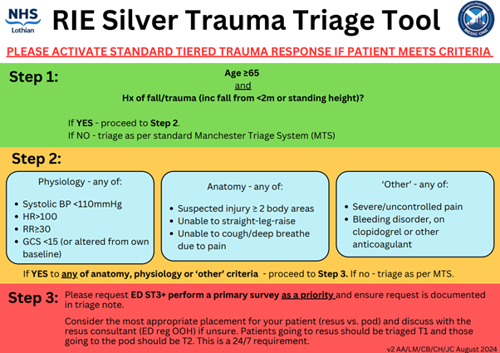

Silver Trauma Triage Tool

Conventional triage systems (e.g. Manchester Triage System) and standard major trauma activation criteria are not always sensitive for older patients. As a result, older adults with significant injuries can occasionally be overlooked or experience delays in imaging or senior review, leading to late diagnoses of significant traumatic injuries.

The Silver Trauma Triage tool provides early flagging of patients aged 65 or over who present with a history of trauma. Rather than automatically defaulting to resus or whole-body CT, the primary goal is to ensure prompt involvement of a senior decision maker. These clinicians can rapidly assess the need for further imaging, specialty input, or escalation of care based on the patient’s presentation, comorbdities and mechanism of injury.

Assessment and Management

Primary survey

Use the CCABCDE approach, with heightened awareness of the nuances in older patients.

- Catastrophic haemorrhage

- Identify and control major bleeding immediately

- Older patients may be on anticoagulants or antiplatelets that can significantly worsen bleeding

- Cervical Spine

- Protect the cervical spine if the mechanism of injury suggests possible spinal involvement or there is any neck pain, altered neurology or reduced consciousness

- Hard collars can be poorly tolerated by older adults. If using, ensure proper sizing and fit, otherwise consider immobilisation in a position of comfort using a soft collar or rolled blankets, e.g. in the case of fixed flexion deformities, to reduce pain, distress and the risk of pressure damage.

- Document the need (or clearance) for C-spine precautions as soon as imaging is complete

- Airway

- Asssess for airway compromise

- Be prepared for difficult airway management in older adults with arthritis, cervical spondylosis or limited neck mobility

- Breathing

- Rib fractures are common in older adults and can be disproportionately painful, leading to hypoventilation or atelectasis, consider early regional analgesia (e.g. ESP)

- Keep an eye on possible undetected pulmonary contusions or pneumonia, especially if the patient is frail or has chronic lung disease

- Circulation

- Hypotension (SBP <110) may be significant in an older patient who is typically hypertensive; remain alert to even subtle changes in BP or heart rate

- Assess for signs of shock- older adults on beta-blockers may not mount the usual tachycardic response

- Reverse anticoagulation early if a major haemorrhage is suspected or confirmed. Use local protocols.

- Disability

- Screen for delirium using the 4AT (see here) if confusion or inattention is new or worsened.

- Check capillary blood glucose. Older adults can present with subtle hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia that compounds trauma severity.

- Exposure

- Fully expose the patient to identify additional injuries.

- Maintain normothermia – older adults are more susceptible to heat loss

- Look for medical alerts, medication lists or personal carer notes that can inform your assessment and management.

- Proactively seek an early collateral history to clarify baseline function and help determine overall goals of care.

The silver trauma triage tool ensures older adults with low-energy mechanisms are flagged early. Prompt senior decision-maker input (ST3+) can help identify subtle injuries, expedite imaging (if needed) and guide next steps.

Many older adults have multiple comorbid conditions (e.g. heart failure, diabetes, renal impairment). This not only impacts resuscitation (fluid management, medication choices) but also increases vulnerability to complications such as acute kidney injury or heart failure exacerbations.

Early involvement of frailty teams, physiotherapy and occupational therapy is key, especially if extended hospital stay or rehab will be needed. A comprehensive geriatric assessment can optimise functional outcomes.

Aim to minimise ward transfers, maintain regular orientation, encourage normal sleep patterns and address sensory deficits (e.g. ensure hearing aids or glasses are in use). Pain control, infection screening and rapid screening for and treatment of constipation or urinary retention also help reduce delirium risk.

Clinical Frailty Scale

Editorial Information

Last reviewed: 01/04/2025

Next review date: 01/04/2028

Version: 2.0